The Journey is your builder’s reference library. Crack open the full archive here → https://6catalysts.substack.com/archive

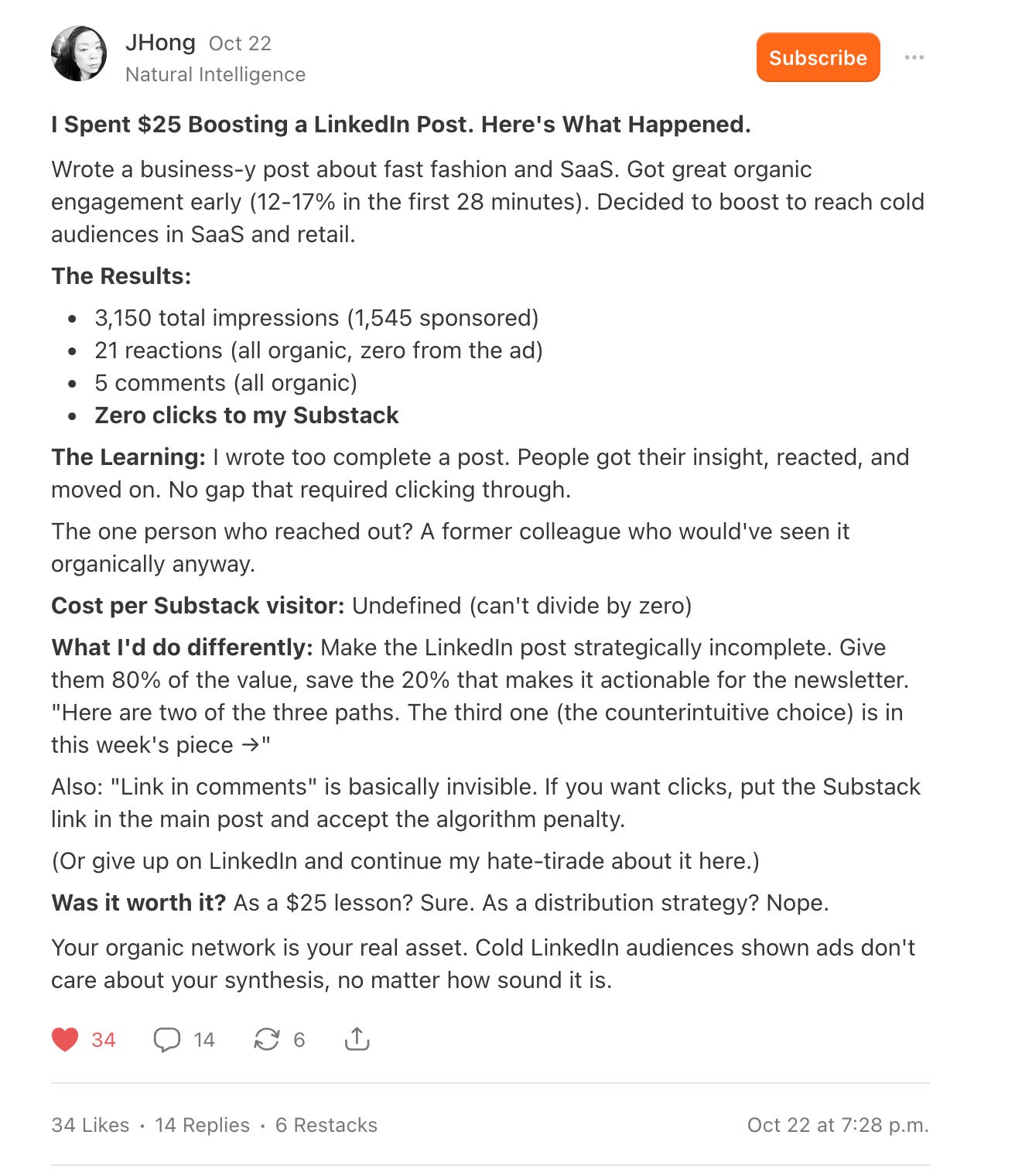

This week’s feature started with a Note on Substack from a fellow human (I think), known as JHong. Whenever I run across things that they’ve posted or talked about, I can’t help but notice how their mind works just a little bit differently from that of most people (in a good way).

After seeing this post, I got a bit struck by the curiosity bug. More specifically, one part of the Note really got all up in my grey matter :

Also: “Link in comments” is basically invisible. If you want clicks, put the Substack link in the main post and accept the algorithm penalty.

… you mean, link placement affects discoverability on LinkedIn? I wonder if the destination of a link also affects discoverability?

Here’s the practical question that I set out to answer :

Which posts will generate more impressions—those with destination links to my LinkedIn Newsletter, or those with destination links to my Substack newsletter?

Wait… What’s this “Penalty” Business?

LinkedIn is a business (owned by Microsoft now, but not always so). It’s also a social media platform. A little bit too much emphasis on the social part for my liking… if I wanted life updates or posts about pets, I’d go to Instagram. But, professional boundaries are clearly a thing of the past and I’m old. So, getting back to it…

LinkedIn primarily makes money on revenue from showing ads to people who are actively using LinkedIn on the web or in the mobile app. Yes, there are subscriptions and services-driven revenue too, but advertising is the main show (if it isn’t, they sure behave like it is).

For LinkedIn to make money on advertising, they need an inventory of impressions to sell to advertisers (in other words, they need eyeballs on site and in-app, and people who are actively scrolling). So, keeping people on linkedin.com or with the mobile app open is a prerequisite for selling that advertising. This builds supply (our attention is the product being sold… or at least a shot at getting our attention, anyway).

This is the fundamental dynamic behind the “algorithm penalty” concept. If LinkedIn’s business is better served with people staying on-site instead of going somewhere else, it stands to reason that it would show content featuring an off-site link less frequently. In other words, they have incentive to algorithmically penalize content which reduces the supply of eyeballs that they can use to sell impressions for advertising.

But does that actually happen in practice?

Well, that’s what I decided to set out and test.

Some Helpful Definitions

In case you’re unfamiliar with web analytics jargon, let’s define some of the terms above… and that we’ll be using throughout this feature :

Impressions : the number of eyeballs that were on a particular post. Kind of. Technically the number of times that a post swung into the viewport on a LinkedIn user’s device, but measurement programs assume that this means that a human saw it.

Reactions : those goofy little emojis that (kind of) represent how people who saw the post felt about it. Lots of ambiguity in this assumption too, but the same limitation applies.

Engagement : scroll interruption, basically. Something about the post caused a viewer to stop and engage with it. Comment, repost, react. It’s (kind of) a pretty good measure of the effectiveness of a piece of content at stopping and making people pay attention to its message.

“Organic” : distribution of content that’s posted by a first party, without direct payment for distribution. For example, I post something on Linkedin in my personal account, and hit the post button.

Link Destination : where the link sends the person who clicked. “On-site” means the destination was on the same domain, “off-site” means the destination was on a different domain.

Gearing Up

When I post about The Journey on Linkedin, Bluesky, Instagram, or Monnett, I’m looking to do two things :

Share what I’ve learned that can help folks start, sustain, or grow a business (or as a professional who’s intrapreneurial).

Build an audience for The Journey, so that the positive impact which I have on the community of builders out there can scale independently of my time and energy.

So… the theory that LinkedIn might algorithmically penalize my posts when I include an off-site link to Substack (The Journey) really piqued my interest. Since I also syndicate post content via a LinkedIn Newsletter, the conditions for an interesting comparison test took shape.

Why does the LinkedIn Newsletter matter?

Substack competes with the Newsletter feature on LinkedIn. Structurally, Substack and LinkedIn Newsletters both help content publishers to do this :

Promote content, attract an audience, and build a subscriber list.

Host rich media content for syndication to subscribers.

Distribute content to subscribers via email and feed.

Distribute content to non-subscribers via an integrated platform with a userbase.

Substack just happens to do these things (and other things) much, much better than LinkedIn Newsletters (in my opinion). This is a bit of a problem for LinkedIn… as the health of its advertising business relies on people staying on-site. So, Substack could be bad for business.

The Hypothesis

Because of the baked-in incentives which prioritize keeping eyeballs on-site, I believed that promotional posts which featured links to my LinkedIn Newsletter would perform noticeably better with respect to impressions.

So, the LinkedIn group would outperform both the control group and the Substack group, generating more impressions at the aggregate level.

The Experiment

While JHong’s experiment revolved around measuring clicks to their Substack, I was more interested in impressions.

As with any good experiment, the devil’s in the details and it’s important to have a baseline condition (control group), and design your test to minimize bias. I outlined the full experimental design and measurement protocol in the spreadsheet used for tracking results, here.

In short… three topically similar posts each day, sending traffic to one of two places (LinkedIn or Substack). For two weeks. With experimental design and process meant to minimize bias and compare apples-to-apples to the extent possible.

Each promotional post had one of :

No link at all, simply text (the control group).

A destination link to the test article published via LinkedIn Newsletters (the LinkedIn group).

A destination link to the test article published via Substack (the Substack group).

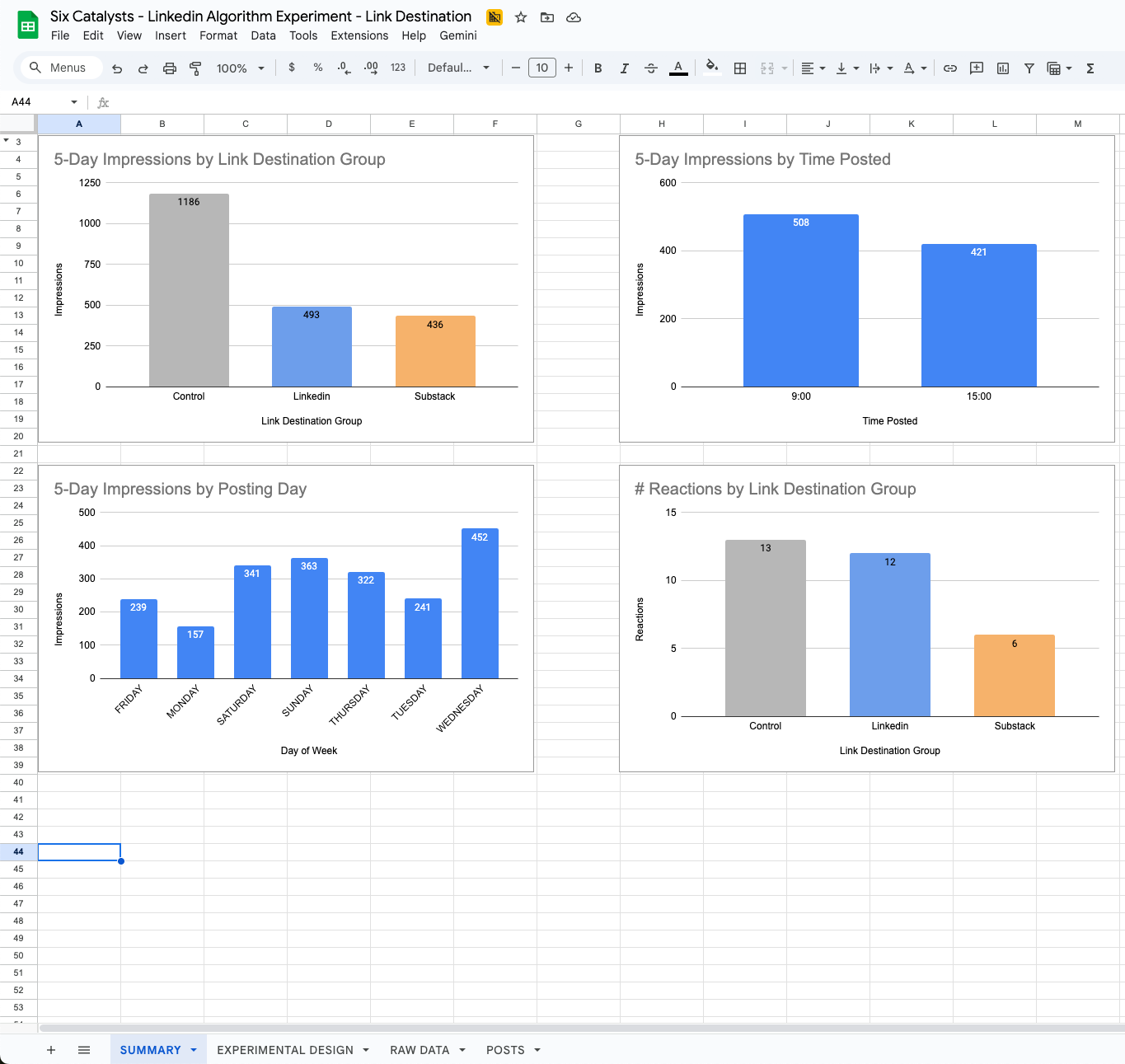

The Results

… were surprising (to me).

The Control group outperformed the test groups by a wide margin, registering a 140% improvement in impressions generated versus the LinkedIn test group (1186 vs 493).

The LinkedIn test group did outperform the Substack test group… but only marginally so at a 13% improvement in impressions generated (493 vs 436). Given the small sample size, I wouldn’t consider this a solid validation of my hypothesis.

This strongly supports the notion that LinkedIn is incentivized to keep eyeballs scrolling on-site because of their advertising business. What surprised me though is that on-site links to the LinkedIn Newsletter destination (which is on the same domain) were penalized roughly the same way as off-site links… even though the LinkedIn Newsletter content would contribute to the supply of eyeballs which advertising could be sold against.

Interesting, eh?

Some other interesting tidbits that came from a cursory analysis of the raw data :

Wednesday was the best day of the week for posting (24% more impressions than the next-best day).

Morning was the best time-of-day for posting (17% more impressions than in the afternoon).

Promotional posts with more than two reactions generated significantly more impressions.

That’s not to say that these trends will hold true for your efforts, content discovery algorithms are complex.

The full dataset and summaries are available here.

Key Takeaways

I think we can reasonably conclude the following :

Organic posts on LinkedIn which contain a link will generate fewer impressions than those which do not.

There will be a “best day” and “best time” for your organic posts, but it might not be “Wednesday” and “morning” like it was for me. The personal and professional routines of your connections and audience will determine these sweet spots. Knowing what the sweet spots are can help you get the most bang for your buck (errr… effort).

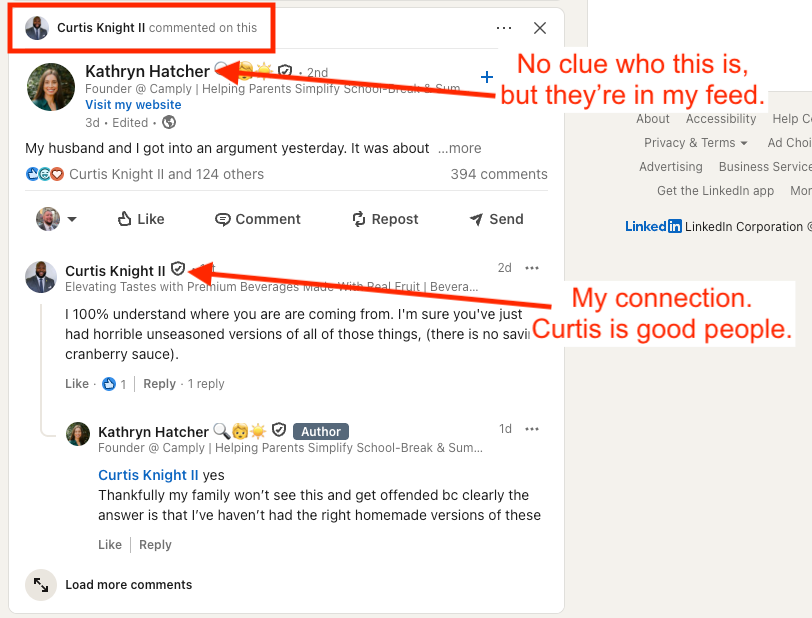

Creating content which attracts reactions and engagement (comments) will amplify an organic post, generating more impressions. Intuitively, this makes sense given that LinkedIn tends to show content to you if someone you’re connected to has interacted with it.

A Burning Question

… if I elected to boost the organic versions of the test group’s posts with paid distribution on LinkedIn, would it/how much of a difference would it make?

Back to the well we go, for another test. I’ll update this post with the answer to that question in a couple of weeks.

Update : Adding a Paid Boost [2025-12-30]

If LinkedIn is a business (it is), and that business primarily makes money by selling advertising (it does), then will paying to boost posts (advertising) sidestep the algorithmic penalty for offsite links?

I suspected so, and ran a small extension to the test to see if there was data to back my hypothesis.

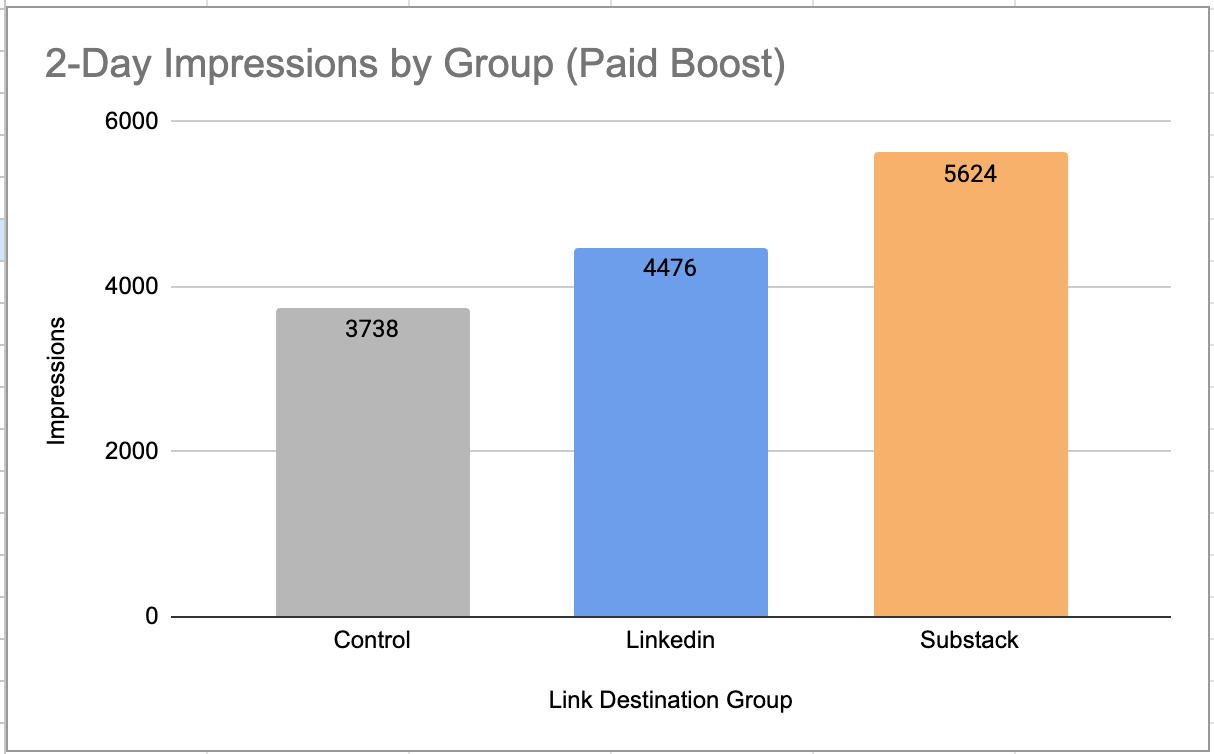

For two days, I paid to boost one ad from each group which had underperformed on reach and also had no engagement on the original organic post.

And as it turns out, the post with the offsite link to my Substack newsletter performed significantly better than the control group (+50.4%) and LinkedIn group (+25.6%). In aggregate, the paid boosts performed significantly better than the organic ones, which was to be expected (+554.3%).

Confirmed :

LinkedIn is a for-profit business… 😉

Including links in posts will limit their organic reach

You can pay-to-play and shortcut the algorithmic penalty with paid boosts (but the business case to do so isn’t clear-cut… always track to metrics that connect to revenue)

If today’s post hit on a challenge you’re dealing with, I’m available for project-based work and ongoing advisory. Book a call and we’ll pressure-test what you’re building : https://calendar.app.google/DKBuFJSjry6NBDeb9.

Feedback

Improving The Journey is a journey in itself, and I’d love your help. Share your anonymous feedback here : https://6catalysts.ca/subscribe/the-journey-feedback/