The Journey is your builder’s reference library. Crack open the full archive here → https://6catalysts.substack.com/archive

Chequebook?

How quaint. Even as I wrote the words, I had a bit of a giggle surfacing in my mind—I haven’t written a paper cheque since about 2011. I still have three unused, pristine books of them in a drawer somewhere around the flat.

… people still use cheques?

Anyway, my turn of phrase may fall flat. I’m OK with that.

This week’s feature is about knowing when to spend the damn money versus doing it yourself (or keeping it in-house). The topic floated up into my brain after reading a piece by Nick Berry recently (check out his newsletter here—it’s a really succinct piece written for owner/operators of businesses from a management perspective).

This sounds like a simplistic issue to be talking about, I know, but there’s some context to it that may resonate with you. When you’re building something from the ground up, cash resources are tight (especially when you’re bootstrapping). It can feel like you’re a wild animal fighting to protect the scraps of what you have in the bank account, so that you can live to fight another day.

When you’re a builder building on fumes, you can easily turn into a resource-hoarder with your bank account. The effect is even more powerful when it’s your own money that you’re using to fund the kickoff of your new venture.

I personally struggle with this, because I’m wired for frugality—which is a useful trait in an entrepreneur until it isn’t.

If we want to make decisions on spending money to invest in what we’re building that are less grounded in fear and other emotional responses… where do we start?

The root issue with this mindset is that the emotional grounding (fear of wasting money) almost always makes us avoid thinking about the opportunity cost—the invisible price of our time and energy… or the time and energy of our team(s).

Maybe you’ll save $1,000 (or Euros, or Pounds) by doing something yourself. But, if it costs you 20 hours of focused time that could’ve generated $5,000 in value through sales or activities closely correlated to revenue, you’re not further ahead even though you might feel a sense of satisfaction or relief.

The concept is easy to put in writing, but how do we apply it to our everyday decision-making?

Think of Time Like an Investment

It helps to think of what you’re building as a portfolio of investments, much like the stock market. You can invest time, money, and attention into it in order to generate returns (create momentum, “move the needle”, build value, et cetera).

So deciding whether or not to buy a solution to something versus DIY’ing it can be broken down into what has lower cost and/or higher benefit overall.

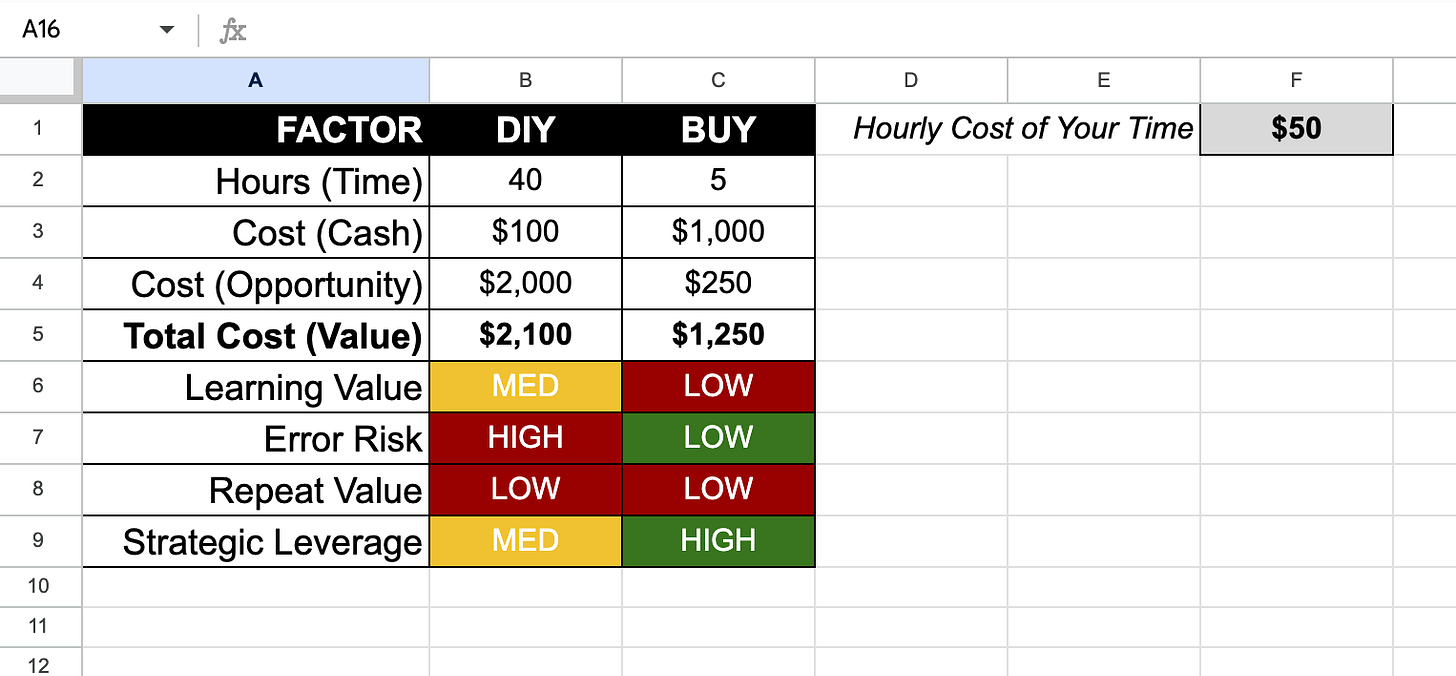

Copy this template to your own Google Drive or download as an Excel file.

Hours (Time) : how many hours of your time might this take?

Cost (Cash) : how much hard cash will you have to spend?

Cost (Opportunity) : the hourly value of your time multiplied by the hours needed.

Total Cost (Value) : cash cost plus opportunity cost.

Learning Value : how much long-term value will you (or the business) receive from it?

Error Risk : how much risk is there if it gets f*cked up? Or, how bad would it be if the outcome was poor?

Repeat Value : is there repeat value in this? I.e., if it’s completed once will it deliver value again without paying or investing more time in it?

Strategic Leverage : does the value of this activity compound? I.e., will it cost less or deliver more with successive times that you complete it?

If you’re not taking a regular salary and are unsure how to value your time, think of it this way—how much do you realistically want to earn in a year from what you’re building. Take that number, subtract planned vacation and leave time from the number of weeks in a year and do some division to arrive at an hourly value.

Desired Earnings / ((52 Weeks - Planned Weeks Leave) * Planned Hours per Week)

= 200000 / ((52-3)*40)

= 102.04 —> this is your hourly opportunity cost if you want to work 40 hours a week with three weeks leave and earn $200,000 a year before taxes and deductions.

Buy or DIY : How to Choose

You choose to buy expertise when :

The problem is non-core but high leverage (e.g. legal, bookkeeping, web development, copywriting).

The expertise gap is wide enough that DIY would lead to mediocre or delayed results.

The decision directly impacts growth or risk exposure.

The Total Cost (Value) is higher for DIY’ing than it is for buying.

You do it yourself when :

The problem is core to your differentiation.

You’ll face that problem repeatedly, so the learning compounds.

The risk of failure is low, and iteration is cheap.

The Total Cost (Value) is higher for buying than it is for DIY’ing.

In the spreadsheet template above, look for lower total cost and more greens than reds. It’s a quick way of approximating the value delivered for buying vs DIY’ing.

Some Examples

You sell insurance. The total cost of DIY’ing a website is $20,000 and the total cost of buying it is $5,000. You likely won’t build another one in the near future, so repeat value is low. Error risk from f*cking it up is medium (reputational risk to the brand). Strategic leverage is low. Buy the solution.

You produce and sell small batch snack foods. The total cost of DIY’ing your packaging design and procurement is $5,000 and the total cost of buying it is $6,000. SKU expansion is slow by design, so repeat value is low. Strategic leverage is low for the same reason. Error risk from f*cking it up is high (regulatory compliance). Buy the solution. Though it would be cheaper to DIY it, the risk from regulatory non-compliance will almost certainly outweigh the $1,000 in savings.

You own a retail shop that sells artisanal soaps and candles (online and in-store). The total cost of DIY’ing eCommerce order fulfillment from the store using your staff is $10,000 and the total cost of buying the solution (from a contract warehouse / 3PL) is $25,000. Repeat value is high (your staff will learn and improve productivity over time if DIY’ing). Strategic leverage is high (you’ll have opportunities for personalized marketing if DIY’ing). Error risk is low (mistakes are common, and can be made right through good service). DIY the solution. At least until you scale to a point where operational constraints in your store make outsourcing fulfillment more cost-effective.

Applying Some Systems Thinking

Another layer to consider is the systemic one, especially as you start adding zeroes to the cost of the task or solution.

Ask yourself :

Is this decision reversible?

Is this problem recurring?

Does solving it myself create an asset (knowledge, intellectual property, or repeatable process)?

Will spending the money to buy it free up time to do higher-value work?

If (1) and (2) are no, but (3) and (4) are yes, that’s almost always the pattern that justifies a buy-it decision.

The Paradox of Control

Many founders mistake control for competence.

It’s a common cognitive bias. Builders and entrepreneurs are do’ers, and it’s natural to think if I can do this, then I must also be good at doing this. As we learn from experience and mistakes, we realize that this isn’t the case… but the instinct lingers all the same.

In a growing company, control scales inversely with impact. The more you insist on doing, the less what you’re building can grow—because the limiting constraints on your time are more pronounced.

Maturing as an entrepreneur often means learning to deploy resources, not hoard them.

Feedback

Improving The Journey is a journey in itself—and I’d love your help. Share your anonymous feedback here : https://6catalysts.ca/subscribe/the-journey-feedback/