The Journey is your builder’s reference library. Crack open the full archive here → https://6catalysts.substack.com/archive

Editor’s Note : this post was originally published on April 6, 2025 and has been updated with the Podcast Edition companion episode.

Ouch!

That’s the polite version of what many manufacturers and international brands said after Wednesday’s announcement at the White House on tariffs. A near-universal tariff of 10% was announced on the low end, with rates of over 50% on the upper end—it appears that only Russia and North Korea are exempted from the initial trade carnage at this point in time. Who knows what will happen in the coming months.

Just to be clear and cut through any lingering misinformation—tariffs are paid by the importer of record (ie, the first buyer of goods inside the US). They’re not paid by the country which produced the goods. They’re not paid by the producer or manufacturer of the goods. And, the tariff is set based on the origin of the goods (where they’re produced or majority-assembled), not where they’re shipped from.

Tariffs are also only assessed on the declared value of tangible goods. Things that exist physically in our environment, which can be touched and used.

This means that the financial burden and increased direct costs associated with these tariffs will be borne primarily by US importers and consumers (as the cost increase, in part or in full, is often passed on to the end-consumer through increased purchase prices).

OK, with that out of the way—

There’s been an explosion of conversation in the past several days around the impact that tariffs will have on individual businesses, trade, and “the economy” (national and global). Many businesses are (rightfully) freaking out and scrambling to ‘run the numbers’ and develop mitigation or adaptation strategies to deflect the brunt of the new tariffs on sales into the US market. The strategy that the White House wants producers to take is simple (at least when said out loud): manufacture your products in the USA.

But, it’s not that simple for most brands and producers. Value-added supply chains (especially complex ones) can’t be redesigned and changed at the drop of a hat. It takes a significant amount of capital and time to develop a new supply chain, and even longer to build the scale needed to drive down costs within that supply chain.

The North American automotive supply chain, for example, has developed over decades and hums along on just-in-time production principles—where you minimize the on-hand inventory of parts so that free cashflow can be maximized and the cash conversion cycle can be as short as possible.

Even if manufacturers were to relocate to the United States en masse, they would still need to pay tariffs on materials and components imported for use in the final assembly of their products. The reality is that not everything which is used in manufacturing a given product exists in the United States, and it’s often not cost-effective to produce certain things domestically for use in a manufacturing supply chain intended to serve a single or regional market.

With that background in mind, what I’m aiming to do with this post is discuss different warehousing approaches for brands and manufacturers based outside of the United States who sell into it, and have the flexibility to adapt their distribution systems. I also put together a rudimentary modelling tool on Google Sheets that you can use to quickly estimate the impact to cashflow for your product’s particulars for each of the scenarios outlined below. If you don’t have a Google account, you can also download the tool for use in Excel on your local workstation.

Given the extreme tariff rate in the US now for some countries of origin, it might make sense for your cashflow position in some scenarios to warehouse goods in Canada or Mexico and ship them into the US upon sale. We’ll look at each approach separately below.

Some Terms to Know

USMCA / CUSMA / T-MEC : the free-trade agreement covering North America which replaced NAFTA in 2018. In the US, the text is titled “United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement”. In Canada, the text is titled “Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement”. In Mexico, the text is titled “Tratado entre México, Estados Unidos y Canadá” (Treaty of Mexico, United States, and Canada).

I’m told that it’s customary for countries to place their own name first in domestic texts related to multilateral treaties—there’s your fun fact for the day.

Third-Party Logistics (3PL) : contract warehousing services provided by a third party. Typically a 3PL will receive, store, account for, and arrange shipment of your goods to your customers.

Duty Drawback : a mechanism in the USMCA / CUSMA / T-MEC agreement which allows importers to claim refunds for some (or all) of the duty and sales tax amounts paid during the import process under certain conditions. Generally this is tied to the re-export of goods to one of the other signatories to avoid “double-dipping” scenarios which would artificially drive up the cost of goods.

Cash Conversion Cycle : basically, the amount of time that it takes a company to convert cash it paid to produce a good back into cash when selling that good (hopefully at a profit). A shorter cycle is generally better for the overall financial health of the business, because that free cash is then available to be reinvested into more inventory, capital equipment, R&D, or expansion.

Last Mile / Last Mile Delivery : delivery from your warehouse location to the end buyer. This part of the cost centre for operating a distribution system is generally the most expensive, so structural changes which shorten the number of miles your goods travel on trucks to get to customers often results in significant savings.

Importer of Record : the entity (person or business) which is responsible for bringing the goods into the destination country. The IOR is responsible for paying any duties, fees, or sales taxes owed. They’re also legally responsible for ensuring that recordskeeping is compliant and declarations to customs agencies are truthful and accurate.

Section 321 Imports : a part of the 19 USC 1321 (“US Tariff Act”) which sets the de minimis threshold for imports into the United States. Imports under this threshold can be imported free of duties and sales tax. This threshold is currently set at US$800, though US CBP announced in January (then delayed to February… then again to March…) that this threshold would be eliminated.

Scenario A : Warehouse Goods in the US

Export your goods to the US for distribution to buyers in the US

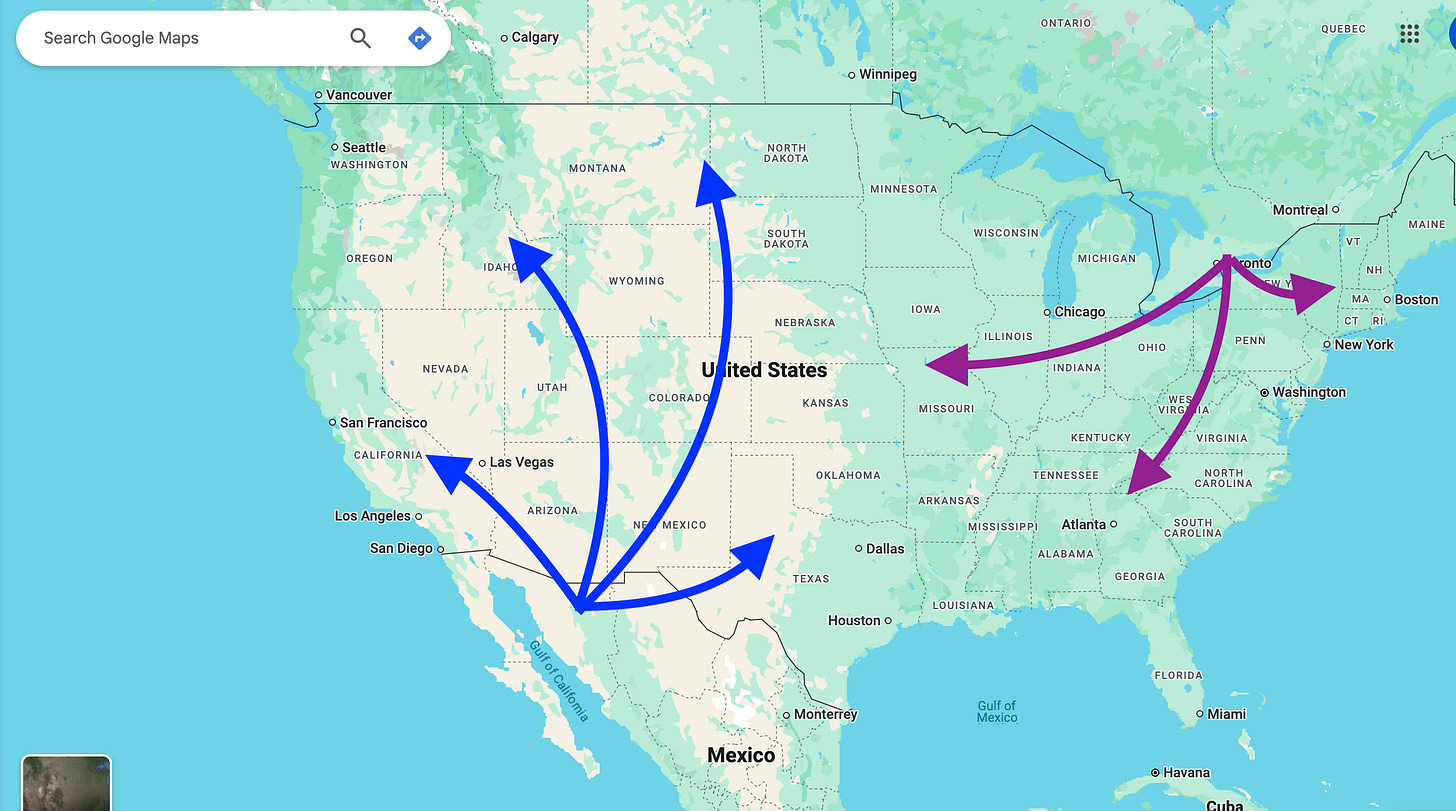

In this scenario, you inventory your goods in the continental United States and ship to customers from one or more locations. Selecting the location(s) to warehouse your goods is driven by an analysis of your customer base to determine optimal proximity to your customers and drive down freight costs for the last mile.

Customers on the east coast can be served from a warehouse on the east coast, et cetera. When I’m advising clients on where to site warehouses (or search for 3PLs), we normally conduct an analysis that combines this information with the cost to cash conversion for siting inventory in one or many locations.

Essentially, we seek to answer the question of is it less expensive overall to warehouse in one, two, or many locations?

For brands that do not want to operate their own warehousing facilities, there are a number of exceptional third-party logistics providers (3PLs) who can be contracted for this function. My good friend Ryan Bennett at 3PL Hub specializes in 3PL searches and procurement in the US market.

Pros

Lowest cost for last-mile delivery to end customers in the US;

Shortest lead times for delivery to end customers in the US;

Lowest complexity for import/export paperwork;

No need to build processes to track amounts eligible for duty drawbacks (CON - because there are none);

No sales tax or VAT payable upon import.

Cons

Duties (tariff amounts) are assessed on the declared value of your imports when they enter the United States regardless of whether or not they’ve been sold to your customers (this will likely be costly under the new tariff regime);

Duties are payable to US Customs (CBP) on the 10th day of the month following import—currently, duties can be deferred if goods are held in a foreign trade zone (FTZ) or bonded warehouse (which is complex, costly, and carries compliance requirements for importers). These solutions are usually unsuitable for sales in the domestic US market;

Duties are now extremely high—10% on the low end, and 50%+ on the high end. If you’re the importer of record into the United States, you’re paying these (back to “ouch!”).

Scenario B : Warehouse Goods in Canada

Import into Canada, warehouse goods there, and ship to the US upon sale.

Given the nearly four decades of free trade in North America, the infrastructure to transit goods from Canada to the USA is quite developed. Highly efficient crossings in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia see a significant amount of cross-border trade each day—and specialized logistics providers operate out of the greater metropolitan areas of Montreal, Toronto, Calgary (or Lethbridge), and Vancouver.

In this scenario, you would warehouse your goods in a location in one of these metro areas and ship orders to the US market upon sale. Like the US, Canada is geographically large—so it may make sense for some brands to site inventory in both Ontario/Quebec and Alberta/British Columbia (depending on the distribution of US orders and a similar cost to cash conversion analysis as described in the last scenario).

Pros

If you also sell in the domestic Canadian market, consolidating your US inventory into Canadian facilities can improve your cash conversion cycle and help reduce the inventory position needed to service both markets;

The duty rates (tariffs) on products imported to Canada are significantly lower than those of the US, given the current protectionist policy position in the US. The average duty for imports to Canada is 8.5%, with a wide selection of duty-free products—particularly for producers in countries covered by a free-trade agreement with Canada (UK/UKTCA, EU27/CETA, and Australasian countries that are signatories to the CPTPP benefit significantly);

Carrier coverage and quality from Canadian providers is similar to that found in the USA, with many Canadian freight companies partnering with US companies for seamless intermodal and last mile delivery;

A robust, efficient mechanism for drawing back duties and sales tax paid upon import, where qualifying (essentially, you can in many cases claim back duties and GST paid to import goods which are ultimately exported to the US);

Duty relief programs exist, affording importers more favourable terms;

The Export Distribution Centre Program allows qualifying entities to import goods designated for re-export on a duty-free basis.

Cons

Last mile delivery costs for shipments to the US will be higher in most cases than for shipments originating from the US;

5% GST—sales tax—is owing on the declared value of goods imported. This is in addition to any duties, but the GST amount can be reclaimed through input tax credits when filing your GST/HST report to the Canada Revenue Agency;

Last mile delivery lead times to US customers will be longer than for shipments which originated in the US;

During peak season or natural disasters, rail capacity constraints on routes connected to ports in Nova Scotia and Quebec can increase the time needed to deliver goods to warehouse locations in Ontario.

Scenario B : Warehouse Goods in Canada

Import into Canada, warehouse goods there, and ship to the US upon sale.

Given the nearly four decades of free trade in North America, the infrastructure to transit goods from Canada to the USA is quite developed. Highly efficient crossings in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia see a significant amount of cross-border trade each day—and specialized logistics providers operate out of the greater metropolitan areas of Montreal, Toronto, Calgary (or Lethbridge), and Vancouver.

In this scenario, you would warehouse your goods in a location in one of these metro areas and ship orders to the US market upon sale. Like the US, Canada is geographically large—so it may make sense for some brands to site inventory in both Ontario/Quebec and Alberta/British Columbia (depending on the distribution of US orders and a similar cost to cash conversion analysis as described in the last scenario).

Pros

If you also sell in the domestic Canadian market, consolidating your US inventory into Canadian facilities can improve your cash conversion cycle and help reduce the inventory position needed to service both markets;

The duty rates (tariffs) on products imported to Canada are significantly lower than those of the US, given the current protectionist policy position in the US. The average duty for imports to Canada is 8.5%, with a wide selection of duty-free products—particularly for producers in countries covered by a free-trade agreement with Canada (UK/UKTCA, EU27/CETA, and Australasian countries that are signatories to the CPTPP benefit significantly);

Carrier coverage and quality from Canadian providers is similar to that found in the USA, with many Canadian freight companies partnering with US companies for seamless intermodal and last mile delivery;

A robust, efficient mechanism for drawing back duties and sales tax paid upon import, where qualifying (essentially, you can in many cases claim back duties and GST paid to import goods which are ultimately exported to the US);

Duty relief programs exist, affording importers more favourable terms;

The Export Distribution Centre Program allows qualifying entities to import goods designated for re-export on a duty-free basis.

Cons

Last mile delivery costs for shipments to the US will be higher in most cases than for shipments originating from the US;

5% GST—sales tax—is owing on the declared value of goods imported. This is in addition to any duties, but the GST amount can be reclaimed through input tax credits when filing your GST/HST report to the Canada Revenue Agency;

Last mile delivery lead times to US customers will be longer than for shipments which originated in the US;

During peak season or natural disasters, rail capacity constraints on routes connected to ports in Nova Scotia and Quebec can increase the time needed to deliver goods to warehouse locations in Ontario.

Scenario C : Warehouse Goods in Mexico

Import into Mexico, warehouse goods there, and ship to the US upon sale.

Similar to warehousing goods for your US customers in Canada, you can do the same in Mexico—the free trade agreement covering North America contains a number of provisions which make transiting goods across borders straightforward, with systems in place between the three countries designed to optimize the flow of tangible goods.

In this scenario, you would import your goods by sea or air into the state of Baja California (likely through the Port of Ensenada, which is optimized for US trade flows). You would then warehouse your goods on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border—a number of border towns host high-quality warehousing space and transportation infrastructure servicing cross-border trade.

Pros

If you also sell in the domestic Mexican market, consolidating your US inventory into Mexican facilities can improve your cash conversion cycle and help reduce the inventory position needed to service both markets;

The duty rates (tariffs) on products imported to Mexico are significantly lower than those of the US, given the current protectionist policy position in the US. The average duty for imports to Mexico is 2.69%;

The US-Mexico border is geographically located very close to large population centres in the western United States—which is very attractive for trade routes between northern Baja California, San Diego, and the Los Angeles areas;

If you plan to remanufacture or upgrade goods you import to Mexico within Mexico, the IMMEX program allows for significant reductions to duties and IVA/VAT paid upon import—if you later export those upgraded goods to another country, like the United States.

Cons

Last mile delivery costs for shipments to the US will be higher in most cases than for shipments originating from the US;

16% IVA/VAT (sales tax) is owing on the declared value of goods imported (this is in addition to any duties);

Last mile delivery lead times to US customers will be longer than for shipments which originated in the US;

Compliance and recordskeeping requirements for importing goods into Mexico are more burdensome than for importing goods to the United States or Canada.

Warehousing in Canada AND Mexico

After running the numbers, you might discover that it makes sense for you to warehouse goods ultimately bound for the US market in both Canada and Mexico. In a multi-site distribution system like this, the division of responsibility would see your Mexican location servicing the western half of the United States (roughly) and your Canadian location (Toronto or Montreal) servicing the eastern half of the United States (roughly).

Managing a multi-site, multi-country system like this wouldn’t be for the faint of heart though. If the numbers suggest that this is advantageous for you, do significant diligence on it and engage your team and stakeholder partners in conversation before committing to it.

Alternatively, you could choose to warehouse goods in Toronto/Montreal for the eastern half of the US market, and in Vancouver/Calgary/Lethbridge for the western half of the US market.

UPDATE ON S321 : On 4th April 2025, the White House announced an executive order signed by President Trump on April 2nd which would eliminate the de minimis threshold for goods with an origin in the People’s Republic of China (including the Hong Kong and Macau Special Administrative Regions), effective on 2nd May 2025. No word yet on de minimis thresholds for other countries, but I suspect that at a minimum this policy will be expanded to include most of the countries in Southeast Asia—in order to combat rules-of-origin fraud using repacking for transshipment and to counter capital flows from the PRC to nearby countries used to set up supply chains in countries which the US administration views as proxies for Chinese policy (regardless of whether or not this is the reality).

Feedback

Improving The Journey is a journey in itself—and I’d love your help. Share your anonymous feedback here : https://6catalysts.ca/subscribe/the-journey-feedback/

Share this post